»Decorative Arts and Design as Expressions of National and Cultural Identity«

18–22 September 2013, Switzerland

Report

How are decorative arts and design used to express a country's character? Objects are often the outward expression of national aspirations. This conference considered the alignment of the decorative arts with national identity - whether ethnic, cultural, or economic. For example, some works, commissioned by court or state patrons, serve as the tools of power and are intended to represent a nation's wealth, taste, and industry. Others carry a message of rebellion or dissent. Traditional or folk imagery was adopted by designers who sought to defend cultural and ethnic values, a pan-European movement known as romantic nationalism. In the twentieth century, modern design became the signature product of the Scandinavian countries, expressive of social and political values, and becoming, not incidentally, a leading export.

Programme

Tuesday, 17 September 2013

| 14.00 - 16.00 | Registration at Swiss National Museum, Landesmuseum Zürich |

| 17.00 | Villa Patumbah, Zurich, welcome. Welcome by ICDAD President Dr. Rainald Franz and ICOM President Switzerland Dr. Roger Fayet |

| Guided tour through villa and Apéro |

Wednesday, 18 September 2013

| Host | Swiss National Museum, Landesmuseum Zürich |

| 08.30 - 13.00 | Registration |

| 09.00 | Opening of the Conference |

| Section 1 | Chair: Rainald Franz |

| 09.30 - 09.50 | Le mobilier de Le Corbusier Arthur Rüegg, architect, Zurich, Switzerland |

| 09.50 - 10.10 | Local relevance and global meaning Meret Ernst, Hochparterre AG Verlag für Architektur, Planung und Design, Zurich, Switzerland |

| 10.10 - 10.30 | Entre restitution et évocation, Les nouvelles salles historiques du château de Prangins Helen Bieri Thomson, Musée National Suisse - Château de Prangins, Switzerland |

| 10.30 - 10.50 | Her Royal Majesty's Design Barbara von Orelli, Universität Zürich, Kunsthistorisches Institut, Zurich, Switzerland |

| 10.50 - 11.10 | Coffee Break |

| Section 2 | Chair: Rainald Franz |

| 11.10 - 11.30 | The Wiener Werkstätte in Zurich 1917 - 1919 Rainald Franz, MAK - Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst / Gegenwartskunst, Vienna, Austria |

| 11.30 - 11.50 | Global Design - Museum Strategies for a New Understanding of Material Culture Mateo Kries, Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, Germany |

| 11.50 - 12.10 | Henry van de Velde - A Belgian in Germany Petra Krutisch, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Germany |

| 12.10 - 12.30 | New German Design of the 1980s Wolfgang Schepers, Museum August Kestner, Hanover, Germany |

| 12.30 - 14.00 | Lunch and welcome by Director of the Swiss National Museum, Dr. rer. pol. Andreas Spillmann |

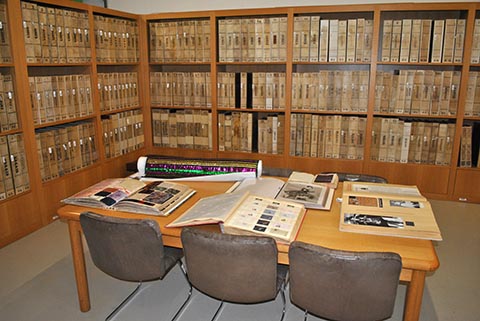

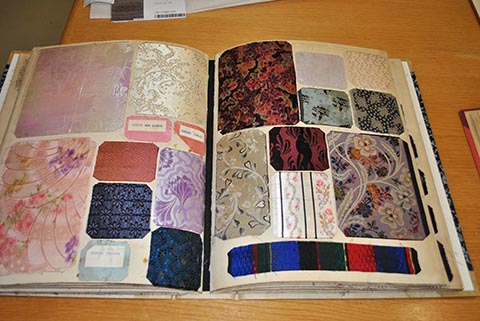

| 14.00 | Departure by coach to the Collection Centre, visit of central storage and conservations labs, Affoltern a. Albis: Textile Collection Abraham AG, Silk (Abraham Silk) |

| 17.00 | Return to Zurich by coach |

| 19.30 | Optional Dinner Zurich City West, Bistro K2 |

Thursday, 19 September 2013

| Host | Swiss National Museum, Landesmuseum Zürich |

| Session 3 | Chair: Wolfgang Schepers |

| 09.00 - 09.20 | Tools of Power and Representation. The Kunstkammer Wien and Its New Installation Franz Kirchweger, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna, Austria |

| 09.20 - 09.40 | Projecting a Modern Nation: Canada at the Triennale di Milano Alan C. Elder, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Gatineau, Quebec, Canada |

| 09.40 - 10.00 | Toys as symbols of nationality. Czech Movement Artěl 1908 Helena Koenigsmarková, UPM - Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, Czech Republic |

| 10.00 - 10.20 | Applied Art as a Means of Change Kai Lobjakas, Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design, Tallinn, Estonia |

| 10.20 - 10.40 | From Iceland: A genuine interest? Harpa Thorsdottir, Museum of Design and Applied Art, Garðabær, Iceland |

| 10.40 - 11.10 | Coffee Break |

| Session 4 | Chair: Helena Koenigsmarková |

| 11.10 - 11.30 | How to promote yourself through decorative arts - a visit to field marshal Count Carl Gustaf Wrangel and Skokloster Castle Inger Olovsson, Skokloster Castle, Skokloster, Sweden |

| 11.30 - 11.50 | Recognition of Quebec's Early Heritage in the Decorative Arts Rosalind Pepall, Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, Quebec, Canada |

| 11.50 - 12.10 | Shaping the Sense of Latvian Identity during the UPS and DOWNS of the 20th century. (Decorative Arts & Design) Velta Raudzepa, The Latvian National Museum of Art / Museum of Decorative Arts and Design, Riga, Latvia |

| 12.10 - 12.30 | Ideas of the Russian Style on the Felix Chopin Bronze Foundry Ludmila Dementieva, State Historical Museum, Moscow, Russia |

| 12.30 | Departure by coach to Basel, lunch bag |

| 14.00 | Welcome Historisches Museum of Basel, guided tours of new permanent exhibition in the Barfüsserkirche: furniture and silver (esp. of the Basle guilds), late medieval tapestries and silk ribbons by the curators Dr. Sabine Söll-Tauchert and Dr. Margret Ribbert |

| 17.00 | Departure to Wildt'sches Haus, visit with Dr. Hans-Christoph Ackermann |

| 19.00 - 21.00 | Gala Concert & buffet at Wildt'sches Haus |

| 21.00 | Return to Zurich by coach |

Friday, 20 September 2013

| Host | Swiss National Museum, Landesmuseum Zürich |

| Marketplace 09.00 - 11.00 |

Chair: Silvia Barisione (Presentations no longer than 10 minutes) |

| The Hungarian ornament - Transformation of the late renaissance flower motives from the representation of the aristocratic culture into the expression of the national identity Anna Ridovics, Hungarian National Museum, Budapest, Hungary |

|

| Echoes and Origins: Interwar Italian Design Silvia Barisione, The Wolfsonian - Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida, USA |

|

| Mikhail Vrubel and Abramtsevo art studio. Formation of the original "Russian style" (based on the collection of M. Vrubel's sculpture in the GCTM of A. A. Bahrushin) Olga Loginova, The State Central Theater Museum of A. A. Bahrushin, Moscow, Russia; Nina Loginova, Moscow State United Museum-Reserve, Moscow, Russia |

|

| Ivan Khlebnikov in State Historical Museum: Triumph Russian style Irina Paltusova, State Historical Museum, Moscow, Russia |

|

| ALMA (where ART MEETS ARTEFACTS): explores artefacts depicted in art as patriotic props Alexandra Gaba-van Dongen, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands |

|

| General Assembly of ICDAD Information of the president on ICDAD |

|

| 11.00 | Departure by coach to Bern, Riggisberg, lunch bag |

| 13.00 | Arrival at Abegg-Stiftung, welcome |

| 14.00 | Visit of Exposition, storage and Villa Abegg |

| 17.00 | Departure for Oberdiessbach, visit of castle Oberdiessbach, Apero |

| 19.00 | Departure by coach to Münsingen, dinner at Wynhus zum Bären |

| Return to Zurich by coach | |

| Conference concludes |

Saturday, 21 September 2013

| Post-Conference Tour to St. Gallen | |

| 09.00 | Departure by coach to St. Gallen |

| 10.30 - 12.00 | Visit of Jakob Schlaepfer, Fabrics, St. Gallen |

| 12.00 - 12.15 | Transfer to Hotel Metropol, St. Gallen |

| 12.15 - 14.00 | Lunch on your own |

| 14.00 - 17.00 | Visit Museum of Textiles St. Gallen, exposition and storage |

| 17.00 | Check in Hotel Metropol, St. Gallen |

| 18.00 | Departure by coach to Ebnat Kappel |

| Evening program with buffet in the Ackerhus Museum of local history | |

| 22.00 | Return to St. Gallen by coach |

| Overnight stay in St. Gallen |

Sunday, 22 September 2013

| Tour to Salenstein Museum Napoleon | |

| 09.00 | Departure by coach to Salenstein |

| 10.00 - 14.30 | Visit Museum Napoleon, castle and gardens Arenenberg |

| lunch in the gardens | |

| 14.30 | Return by coach to Zurich Airport and Zurich main station |

| 15.30 | Arrival Zurich Airport |

| 16.00 | Arrival Zurich main stations |

| Post-Conference Tour concludes |

Lectures

Echoes and Origins: Italian Interwar Design

Silvia Barisione

The Wolfsonian - Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida, USA

In Fall 2013, on the occasion of the year of Italian culture in the US, the Wolfsonian is organizing Rebirth of Rome, a program of three interrelated exhibitions that examine the aesthetics of dictatorship in interwar Italy. Each exhibition will address responses to the challenges of modernity, as seen in the over 200 objects of public works, mural paintings, architecture, design, and decorative arts in Italy in the 1920s and 1930s, drawn from The Wolfsonian's collection.

The exhibition Echoes and Origins presents a selection of furniture, ceramics, glass, graphic and product design, and industrial objects which offers a survey of the aesthetic pluralism permitted by the Fascist regime which sought to turn a diverse population into a unified nation, combining notions of the Imperial Roman past with the spirit and technology of modernity.

Following the brief success of the Liberty style at the turn of the twentieth century, craft production in Italy largely returned to the replication of historical styles. In an attempt to carry the Italian applied arts out of this period of stagnation, the Biennale internazionale delle arti decorative (International Biennial of the Decorative Arts) was established in Monza in 1923. Divided into regional sections, these recurring expositions provided a public platform for the display of contemporary currents, with artisans drawing on local traditions in their efforts at renovation and modernization.

With its change from a biennial to a triennial in 1930, thematic organization replaced arrangements by region, giving increased emphasis to specific materials and engagements with international modernism. Subsequent triennials were held in Milan, making them Italy's principal means of circulating new ideas in the applied arts as well as interior and architectural design. Two keys trends in architecture, Novecento and Rationalism, were especially influential. Novecento architects aimed at updating and clarifying the neoclassical tradition, while Rationalists pursued the tenets of the International Style. Despite their differences, both approaches aspired to the creation of a modern Italian style according to the concept of Italianitá (Italianness) asserted by the Fascist regime. Mussolini's government always maintained an ambiguous attitude toward architecture and the arts, adopting a policy of trasformismo that enabled it to appropriate diverse stylistic tendencies and thereby accommodate a certain degree of free artistic expression.

Commercial representations of progress and modernization, especially with respect to Italy's quest for technological supremacy, demonstrate the same dichotomy of tradition and innovation. Advertising campaigns for new products alternated allegorical scenes inspired by classical mythology with avant-garde idioms introduced by the Futurist movement.

Entre restitution et évocation, Les nouvelles salles historiques du château de Prangins

Helen Bieri Thomson

Musée National Suisse - Château de Prangins, Switzerland

Quinze ans après son ouverture au public, le château de Prangins renoue avec son passé en inaugurant une série de salles historiques. A partir de deux documents d'archives capitaux pour l'histoire de l'édifice, un inventaire de biens et un journal, l'équipe chargée du projet a recré é un décor vraisemblable pour évoquer les salles de réception d'une demeure seigneuriale en Pays de Vaud à la fin du XVIIIe siècle.

Le principal défi de l'opération résidait dans la quasi absence de mobilier d'origine, celui-ci ayant été dispersé au fil du temps. La présentation se focalisera sur les différentes manières dont les collections de mobilier et d'art décoratif du Musée national suisse ont été sondées et exploitées pour fournir des objets de substitution représentatifs. A la lumière de quelques exemples seront montrées les potentialités mais aussi les limites d'un tel exercice.

Ideas of the Russian Style on the Felix Chopin Bronze Foundry

Ludmila Dementieva

State Historical Museum, Moscow, Russia

One of the most important trends in the development of Russian decorative art in XIX century was to create national Russian style, based on traditional images. Intensive efforts of Russian artists in this direction were vivid evidence and reflection in the expression of national identity. The evolution of the national Russian style took place at several levels, in accordance with aesthetic views of different social groups.

The possibility to trace different ways in the revalue of the traditional cultural legacy gives rare examples of bronzes made on the most renowned Saint Petersburg foundry of Felix Chopin, which are now in the collection of the State Historical Museum in Moscow. One course of the formal Russian artistic style was reflected in the series of so called arks, which were ordered by the imperial Russian court for the custody of the most ancient and important state documents and tsarist letters.

The design of the arks was created by the famous Russian artist Feodor Solntsev (1801-1892) in 1852-1853. He was the first to focus his attention on early Russian ornamentation and traditional forms as the chief elements of a style. Later, on the basis or this trend, so called "Kremlin" style will appear.

Another trend was based on the stylization of historical images. In order to spread it the production of so called Gallery of Russian princes, tsars and emperors was organized. The Gallery of 64 bronze busts was casted on Chopin foundry in 1867-1878. Later, in the middle of 1870-1880 Chopin began to combine stylized images and the motifs from folk Russian art, characteristic of embroidery and carving. Impressive examples of such objects were created by the famous Russian sculptor Evgeny Lanceray and leading architects of this era.

Projecting a Modern Nation: Canada at the Triennale di Milano

Alan C. Elder

Canadian Museum of Civilization, Gatineau, Quebec, Canada

The Triennale di Milano had been instituted in the 1920s to present architecture, decorative and industrial arts. When Canada received an invitation from the fair's organizers in 1951, the Canadian trade secretary in Rome was less than enthusiastic about Canada's participation, in part because of the shortness of preparation time and expense, but also because of his perception of the shortcomings of Canadian design.

Three years later, though, Canada did participate in the Tenth Triennale. This display, organized by the National Industrial Design Council (NIDC), consisted of two rooms - one, a living-dining room; the other, a kitchen. A separate outdoor space was also included as a way of representing the familiar trope of Canadians being at one with nature. The two rooms were meant to demonstrate the design possibilities for the average accommodation of Canada's newly formed postwar families.

This interest in the quotidian was also reflected in the 1957 display that focused on the development of the "new town" of Kitimat by the Aluminum Company of Canada (Alcan). Along with furnishings and photographs taken of the workers' and guests' quarters were objects that had received NIDC Design Awards (a Canadian version of the Good Design awards).

These two displays were meant to represent a revitalized Canadian identity to an international audience. My paper will look at the furniture and furnishing used in the 1954 and 1957 displays and their representation of contemporaneous social concerns.

Local relevance and global meaning

Meret Ernst

Hochparterre AG Verlag für Architektur, Planung und Design, Zurich, Switzerland

It may be astonishing at first sight but there is scarcely a country so obviously and strictly designed as Switzerland. Countless regulations define the design of public spaces. New designs always run into already occupied and regulated terrain. This was not always the case. Up until the 20th century, poverty was wide-spread in Switzerland, and the country was a land of emigration. Yet with the development of the industrial sector and the service sector a little later on, it became one of the richest societies in the world. There were few ruptures in this steady upward development despite rapid changes in technology and in the standard of living. Neither war nor natural catastrophes could hold up the country's economic and technological progress.

What about design? Significant for this steady progress is the label Good Form. The roots of «Good Form» extend back to the 1930s. At that time mechanisation and rationalisation of products was called for: A move away from «fashionable seasonal articles» towards «lasting standard products».

But there is no land without ornament or symbol, not even rational Switzerland. Even among the classics of functional origin there are signs: red and obvious as we can see in Herman Hilfikers well known Railway clock. Still, Swiss design is considerd to be discreet and to persist in the service of usefulness. So much can be said about the nature of local design. To stand out is not a welcome characteristic in a land so scrupulously mindful of political and cultural balance.

A closer look on what designers do show that designing is a complex process. It is driven by different requirements. Designers must compare their designs to the manufacturer's image, give the product an appearance which can carry the brand. In the end, it is often not the designer who determines what the brand is, but the consumer whose expectations are analysed in exhaustive market research. Out of necessity design acquired strategic knowledge to sustain its scope and freedom. This did not go unnoticed in critical circles: Hence the criticism moved from the evaluation of a single product towards criticism of the context, in which a product endows its effect and its meaning. This is what Design Theoretician Lucius Burckhardt meant with the notion «Design is invisible».

Considering this situation, can we still talk about national identity reflected in design? What about the fact that design is often conceived at one place while the products are manufactured and consumed all around the world? How do contemporary designers cope with the fact that design is part of a globalized economy? And what about the highly estimated quality of local rootedness? The input will talk about Swiss designers and producers trying to give answers to those questions.

The Wiener Werkstätte in Zurich 1917-1919

Rainald Franz

MAK - Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst / Gegenwartskunst, Vienna, Austria

Between 1917 and 1919, the Wiener Werkstätte was running a shop in the fashionable Bahnhofstrasse in Zurich, fully decorated and designed by Dagobert Peche (1887-1923), the most influential designer in the Wiener Werkstätte next to Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser in his lifetime. This extraordinary effort of the "WW" had aesthetic and economic reasons and was one of the actions taken and supported by Austrian State shortly before the post-Habsburg-period in order to secure a future after the breakdown of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Decorative Arts were used as "ambassadors" of a typical Viennese style and Austrian Aesthetic. The lecture documents this period with original pictures from the archive of the "Wiener Werkstätte", housed in the MAK.

Tools of Power and Representation. The Kunstkammer Wien and Its New Installation

Franz Kirchweger

Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna, Austria

In 1991 the Department of Sculpture and Decorative Arts of the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien was renamed as "Kunstkammer"; a term known to have been used for the collections of the House of Habsburg since the first half of the 16th century. In 1991 the name was chosen despite of the fact, that the former broad range of objects did not exist anymore and that the actual installation (since 1964) was based on rather strict art-historical categories.

With the new installation (opened in March 2013) the challenge was taken to put a special focus on the idea of collecting and the history of the former "Kunst- und Schatzkammern" of the Habsburgs that were always understand as tools of princely power and representation and an expression of identity for the family and their territories.

Henry van de Velde - A Belgian in Germany

Petra Krutisch

Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Germany

The Germanisches Nationalmuseum keeps a number of items from the vast oeuvre of Henry van de Velde (1863-1957). The core of the Nuremberg collection consists of furniture from the study of the publisher Ludwig Loeffler, a co-owner of the Berlin publishing house of Loeffler & Schuster (est. 1895). Loeffler was one of those German customers who engaged van de Velde already in the years before 1900 and - ultimately - helped the young Belgian artist together with a small and elite circle in Berlin to achieve international recognition.

Applied Art as a Means of Change

Kai Lobjakas

Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design, Tallinn, Estonia

One of the central discussions in the Soviet society from the mid-1950s onwards was fulfilling the needs of inhabitants, raising the living standards by providing better choice of consumer products and improving the everyday environment through their design.

Integrating art into everyday life, making art part of life patterns, available for people, was seen as an ideal. Related to that the position of the art fields that really were affecting and shaping the everyday environment became considered highly important. In initial discussions in the 1950s, applied art was seen as a high quality model for this, it was applied art that had to play a role in redefining the new everyday life, in providing a model for good taste and design.

An often-quoted task in this was the improvement of the selection and design features of mass consumer goods. This had to be carried out by the applied artist who traditionally was trained in the State Art Institute as a specialist for industrial production, working for already existing and potential future factories. Discussions at that period revolved around the need to engage the applied artist more to the process of production, applied artist to be collaborating with the industry was seen as a key to enliven the expected process. From the 1950s artists were sent to production facilities and factories on a regular basis. By the beginning of the 1960s there were more than 100 artists working in factories as industrial artists, a number that was constantly growing. And the picture started to change.

In my talk I would like to draw attention to the applied and industrial art of Soviet Estonia seen as means for improving the everyday environment and introduce some examples supporting this ambitious idea. I would also like to trace the changing meaning of the notions and positioning of applied art and design in Soviet Estonia throughout the 1950s and 1960s. If initially, in the early 1950s, these concepts were intertwined and often used as synonyms, then by the 1960s they clearly started to refer to separate fields. The changed industrial and productive course in the mid 1960s brought to the centre the notions of industrial art and design.

Mikhail Vrubel and Abramtsevo art studio. Formation of the original "Russian style" (based on the collection of M. Vrubel's sculpture in the GCTM of A.A. Bahrushin)

Olga Loginova

The State Central Theater Museum of A. A. Bahrushin, Moscow, Russia

Nina Loginova

Moscow State United Museum-Reserve, Moscow, Russia

Vrubel's creativity and art of the other artists of the last quarter of the XIX century, who worked in the art studios in Savva Mamontov's Abramtsevo estate, had a great influence on the Russian style.

"Russian style" encompasses all that is famous for Russia for many centuries. Here are peasant folklore and imperial luxury, bright oriental color use and traditional arts and crafts. This style had a great aims.

On the one hand, - it was intended to unite the nation by gathering all the features of a huge multi-national country, elaborating in this way cultural and national identity. By the means of art it was possible to express belonging to Russian statehood and culture, express the concept of his "originality", i.e., difference from the others.

On the other hand, - it could help for Russian culture to take its own place among the world's cultures, expressing its social and artistic values for the world.

"Abramtsevo artistic circle", established in 1878, played a major role in the development of Russian national culture of XIX - n. XX centuries. The initiator of its creation was the famous industrialist and billionaire Savva Mamontov. He was greatly supported by the Russian government, which shared his artistic preferences. It was he who became the patron of the workshops, initiating the creation of many artworks in the "Russian style".

The most characteristic feature of this art community was an appeal to ancestral Russian crafts, revival and active use in the working process. As he result there were founded two workshops: joinery and ceramic studio. The particular interest was paid to the development of the applied arts. People from the villages in the vicinity of the Abramtsevo were involved to the work; they received the skills in a local art school. It had a big impact: art school still exists till today as the College of Arts and Industrial Design.

The Abramtsevo production had very important industrial character. Items created in the studio (many of them were real masterpieces) had the great demand, they were available to everyone. As the result the "Russian style" was assimilated by the broad masses.

Mikhail Vrubel devoted many years of his life and work to the Abramtsevo workshops. He interpreted and modified the "Russian style" by recreation of peasant life objects and traditional ornamental forms into the new plastic system. Working in the ceramic workshop Vrubel created numerous sculptures on the theme of Russian folklore.

Collection of the GCTM of A.A. Bahrushin has seven sculptures in the majolica technique. Here are the heroes of Russian folk tales and myths: Sadko, Volkhova, Berendey, Kupava, Mizgir and Lel'.

M. Vrubel and his cooperation with the Abramtsevo art studios contributed much to the development and establishment of the "Russian style". The stile in its turn influenced into the national and cultural identity ideas formation, and became the "calling card" of the Russian state to the international community.

How to promote yourself through decorative arts - a visit to field marshal Count Carl Gustaf Wrangel and Skokloster Castle

Inger Olovsson

Skokloster Castle, Skokloster, Sweden

Visitors to Sweden in the beginning of the 17th century and in the last quarter of the same century would have had totally different impressions of what they saw. The reason for this is certainly the Swedish success in the Peace of Westphalia 1648. For the first time, Sweden had a firm grip on the development of Europe and a seat in the German Parliament as owning Pomerania. This influence and development had an impact on the decorative arts and the cultural identity.

From a wooded peninsula in Lake Mälaren rises the impressive white façade of Skokloster Castle, one of the largest 17th-century buildings in Sweden. Above the entrance, there is a segment gable with the coat of arms of its founder Count Carl Gustaf Wrangel (1613-1676), painted on a stone relief and with a carved trophy on the top. No one approaching the castle could be unaware of its owner.

Sweden needed a new international way to communicate through emblems, and decorative arts became the tool to reach the goal to show the greatness of Sweden and the individual persons, in this case Carl Gustaf Wrangel. He was not unique in his desire to reflect Europe and the world. In the 17th century, Skokloster Castle was only one of many showpieces of this kind - perhaps the one most skillfully carried out - but above all, the only one to be so wellpreserved to this day.

In my presentation, I would like to show how the theme of this member of the aristocracy is shown, not only in the façade but also in the interior decoration, such as in the elaborate stucco ceilings and stoves of the state apartment. Identity through decorative arts is better performed at Skokloster than ever before in Sweden.

Ivan Khlebnikov in State Historical Museum: Triumph Russian style

Irina Paltusova

State Historical Museum, Moscow, Russia

The report is dedicated to silver articles produced by the Moscow factory of Ivan Khlebnikov. In the second half of the 19th century the factory of Ivan Khlebnikov was one of the leading factory in Moscow. Alongside the articles of everyday use the factory produced wonderful churchplate. Khlebnikov continued the tradition of creating sculpted groups on subjects from the life of the people (i.e. peasants) and various utensils with cast details «in Russian fashion ».

The works of Ivan Khlebnikov were distinguished for their high artistic merit and displayed at the All-Russian and the world exhibitions, it often won first prizes. The workers at this factory were very skillful in chasing, engraving, nielloins, enamelling.

Recognition of Quebec's Early Heritage in the Decorative Arts

Rosalind Pepall

Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, Quebec, Canada

Early in the twentieth century, Canadian artists, architects and collectors began to recognize the value of Quebec's heritage in seventeenth and eighteenth-century furniture, silver and textiles, which were uniquely Canadian in their combination of English and French references (form, materials and decorative motifs). Beginning in 1932, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts was one of the first museums to purposefully buy early Quebec decorative arts for its collection, in order to preserve the craft traditions that were rapidly disappearing and to serve as inspiration for modern artisans. The members of Montreal's Canadian Handicrafts Guild, established in 1905 in the spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement, played a role in encouraging the museum to collect Quebec art. The Guild promoted both Quebec's historic and contemporary crafts, including the work of the First Nations, by holding exhibitions and sales of these Canadian arts.

The importance of Quebec's heritage in providing inspiration for contemporary work was evident in the small "museum" of early Quebec decorative arts at Montreal's cabinetmaking and interior decorating school, the École du Meuble, established in 1935. The director of the school, Jean-Marie Gauvreau, encouraged the study of historic Quebec applied art and the use of Canadian woods in the development of modern Canadian design.

Using illustrations of early Quebec furniture, silver and textiles, the lecture would discuss the development of interest in these works in the first years of the twentieth century, peaking in the 1930s, when museums began to recognize and exhibit this work as a representation of true Canadian design.

Shaping the Sense of Latvian Identity during the UPS and DOWNS of the 20th century (Decorative Arts & Design)

Velta Raudzepa

The Latvian National Museum of Art / Museum of Decorative Arts and Design, Riga, Latvia

The speech will consist of several parts. It will reflect the theme chronologically and in different aspects: historical, political, economic, mental, philosophical, creative, etc. It will point out the most characteristic examples of shaping the Latvian national identity in decorative arts and design of the 1920s-1930s (e.g. within the "Latvian national style" as well as examples of modernism); characterize its specifics during the new political power - Soviet ideology - in the 1950s-1960s; will give the notion of new stylistic principles in developing the theme via exhibition politics in the 1970s-1980s as well as the new perception of the idea of the national identity at the end of the 1980s-1990s, while regaining the independence of Latvia. At the end of the speech the change of priorities within this very important topic at the beginning of the 21st. c. in Latvia and its neighbouring Baltic countries as well as its future perspectives will be discussed.

The speech will be richly illustrated with the Power Point presentation. Examples will be taken from the Latvian National Art Museum/ Collection of the Decorative Arts and Design Museum and private collections.

The Hungarian ornament - Transformation of the late renaissance flower motives from the representation of the aristocratic culture into the expression of the national identity

Anna Ridovics

Hungarian National Museum, Budapest, Hungary

From the end of 18th century, in the 19th century when the national states were born the question of the national style as an expression of the national identity have got more and more importance. In the spirit of the historicism the memories of the great historical past of the country, the neo-styles with their special meaning certified the present significance. On the other hand the Arts and Crafts movement preferred the values of the historical quality handcrafts against the industrial mass productions.

After the 1851 World Exhibition in London was born the first Arts and Crafts Museum in South Kensington (1852). The museum's historical collection served as study example of the contemporary crafts. After Wien (1867), Berlin (1869) at Budapest was born a new "Gewerbemuseum" in 1873. Hungary received a lot of inspiration from the idea of the "national cottage industry" announced by Jacob Falke at world exhibition of Wien in 1873. Trade schools and cottage industry cooperatives were established.

In this time began discussions about the "Hungarian style" - especially in writings of Ferenc Pulszky and József Huszka. There were organised roundtours around the country to collect the ornaments for publishing in pattern books as inspirativ models to revive the Hungarian industry according to the 19th century researches of ornaments founded by Oven Jones. The forgotten treasury of the renaissance motives on ceramics, tin and silver artifacts and especially on embroideries was tried to evoke and spread again into wider range. On the other hand a special interest was addressed for the folk art expressing the national character.

This is the time of the birth of ethnographical collections and the foundation of the Ethnographical Museum in Budapest. The rich treasury of the stylized Hungarian folk motives rooted also into the late renaissance decorative art, into its ornaments with eastern origin. This time became popular the ideas about the estimated connection between the Hungarian folk art (XIX. cent) and between the decorativ art of the ancient Hungarian settlements from the period of conquer (IX. cent.) and before.

Publications of József Huszka "Hungarian decorative style" and "Hungarian ornaments" gave a great impulse for the Hungarian decorative art at the turn of the 19-20th century, we can examine those influence on the glasses, ceramics, furniture, textile and on the architecture too. This gave a special national character for the Hungarian Art Noveau.

New German Design of the 1980s

Wolfgang Schepers

Museum August Kestner, Hannover, Germany

Nearly everybody dealing with design history of the 1980s knows Alchimia and Memphis. But nearly at the same time in Germany came to light a design, which was typically for the northern situation: the so called New German Design. Instead of being supported by industries new German Designers went back to handmade objects, one off items and "doing it yourself".

On one hand these designers or artists searched for an authentic not estranged manner for realizing their own ideas. On the other hand this was - as well as in Italy - a kind of subversion or better protest against the so called "Gute Form" (bel design). It's - I think - typically for the movement not to wait for great industries but instead to use their own skills. These young designers oscillated between traditional handicraft and art.

Ready made design was on vogue as well as using unconventional materials like steel, concrete or semi-finished products.

Inspirations came from "Heimat", "Autobahn", super markets or contemporary music (for example: Kraftwerk). At that time I curated some exhibitions which had an incredible media success (I could give some examples).

Conclusion: National identity was at that time neither an idea from the state nor a goal of the creatives.

From Iceland: A genuine interest?

Harpa Thorsdottir

Museum of Design and Applied Art, Garðabær, Iceland

During the last ten years there has been a radical shift in the field of design in Iceland. As one of the Nordic countries, Iceland has been an outsider when it comes to the label "Nordic Design". Its national identity does mostly lie in people's vision of a country with wild nature and beautiful landscape. This small nation has nevertheless made its way in many senses, and has important nature resources to work from, both in material and in other ways, in design and the decorative arts. Today we see for the first time a thorough re-evaluation of a multiple heritage through our young designer's research, which often results in finished works, produced for a small scale local market. The financial crisis which started in 2008 made another shift in the lives of Icelanders and this paper will also discuss the impact it had on seeking our roots through an older Icelandic heritage, upontil now, mostly neglected and even forgotten.

Her Royal Majesty's Design

Barbara von Orelli

Universität Zürich, Kunsthistorisches Institut, Zurich, Switzerland

In 1849, Henry Cole published in The Journal of Design and Manufactures the design for a centrepiece, conceived by Prince Albert. This centrepiece, displaying a very personal iconography, had been commissioned by Queen Victoria and executed in 1842/43 by R. & S. Garrard in London. In the accompanying text, Cole explains that he had been explicitly asked to make a critical examination of the artwork. The following text, written by Cole, reveals, that discussing the design by Prince Albert, emphasizing its positive and negative aspects, becomes a very difficult task. Because being conceived by Prince Albert, the centerpiece is no longer object, but becomes a sort of substitute of its conceiver by the fact, that pronouncing a critical statement on this object, would have immediately been transferred to the person of the prince itself, being the one who misconceived or badly conceived the object.

So Cole had quite a hard work. Being asked to discuss the centerpiece in his journal, under such circumstances, he could hardly refuse to do so. He was conscious of the fact, that every negative remark immediately would be referred to the person of the Prince itself and therefore would be a lèse-majesté. Cole, as a clever man, found the solution in discussing e object by referring to the categories of Vitruv and in this way introduced a sort of atemporal dimension in his critical discussion of Prince Albert's centerpiece.

Participants

Ellenor ALCORN

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Silvia BARISIONE

The Wolfsonian - Florida International University, Miami Beach, USA

Ilsebill BARTA

Hofmobiliendepot-Möbel Museum Wien und Silberkammer Hofburg Wien, Austria

Helen BIERI THOMSON

Musée National Suisse - Château de Prangins, Switzerland

Monica BILFINGER

Bundesamt für Bauten und Logistik, Berne, Switzerland

Henriette BON

Schule für Holzbildhauerei Brienz, Archiv und Sammlung, Brienz, Switzerland

Bernadette DE LOOSE

Design museum Gent, Belgium

Ludmila DEMENTIEVA

State Historical Museum, Moscow, Russia

Alan C. ELDER

Canadian Museum of Civilization, Gatineau, Quebec, Canada

Rainald FRANZ

MAK - Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst/Gegenwartskunst, Vienna, Austria

Alexandra GABA-VAN DONGEN

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Daria GANTSEVA

Moscow, Russia

Nina GANTSEVA

Stroganov MSAID Museum, Moscow, Russia

Christiane HEISER

Projekt MIK, Mies van der Rohe in Krefeld e.V.

Peter HONEGGER

Kunsthistoriker, Berne, Switzerland

Ingalill JANSSON

Stiftelsen Hallwylska museet, Stockholm, Sweden

Franz KIRCHWEGER

Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna, Austria

Helena KOENIGSMARKOVÁ

UPM - Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, Czech Republic

Petra KRUTISCH

Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Germany

Martina LEHMANNOVA

Muzeum hlavního města Prahy, Prague, Czech Republic

Kai LOBJAKAS

Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design, Tallinn, Estonia

Nina LOGINOVA

Moscow State Integrated Museum-Reserve, Moscow, Russia

Olga LOGINOVA

A. A. Bahrushin State Central Theater Museum, Moscow, Russia

Inger OLOVSSON

Skokloster Castle, Skokloster, Sweden

Irina PALTUSSOVA

State Historical Museum, Moscow, Russia

Rosalind PEPALL

Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, Quebec, Canada

Velta RAUDZEPA

Museum of Decorative Arts and Design, Riga, Latvia

Anna RIDOVICS

Hungarian National Museum, Budapest, Hungary

Mienke SIMON THOMAS

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Christina SONDEREGGER

Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum, Landesmuseum Zürich, Switzerland

Deborah THOMPSON

Falkenbergs museum, Falkenberg, Sweden

Harpa THORSDOTTIR

Hönnunarsafn Íslands, Museum of Design and Applied Art, Garðabær, Iceland

Sabine THÜMMLER

Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin, Germany

István TÓTH

Budapest, Hungary

Barbara VON ORELLI-MESSERLI

Universität Zürich, Kunsthistorisches Institut, Zurich, Switzerland

Ines WAGEMANN

Kunst- und Architekturhistorikerin, Darmstadt, Germany

Lecturers

Hans Christoph ACKERMANN

Wildt'sches Haus, Basel, Switzerland

Karin ARTHO

Heimatschutzzentrum in der Villa Patumbah, Zurich, Switzerland

Meret ERNST

Hochparterre AG Verlag für Architektur, Planung und Design, Zurich, Switzerland

Anna JOLLY

Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg, Switzerland

Ursula KARBACHER

Textilmuseum, St. Gallen, Switzerland

Jost KIRCHGRABER

Ackerhus, Ebnat-Kappel, Switzerland

Markus LEUTHARD

Swiss National Museum, Collection Centre, Affoltern, Switzerland

Michaela REICHEL

Textilmuseum, St. Gallen, Switzerland

Margret RIBBERT

Historisches Museum Basel, Switzerland

Michele RONDELLI

Jakob Schlaepfer, St. Gallen, Switzerland

Arthur RÜEGG

Architect, Zurich, Switzerland

Sabine SÖLL

Historisches Museum Basel, Switzerland

Andreas SPILLMANN

Swiss National Museum, Landesmuseum Zürich, Zurich, Switzerland

Sigmund VON WATTENWYL

Schloss Oberdiessbach, Oberdiessbach, Switzerland

Images